The book I will look at today is a much earlier book, Tales from the Story Hat, published in 1960 with illustrations by Elton Fax; it's available for digital lending (two copies) from the Internet Archive.

Aardema was born in 1911, and she worked as a elementary school teacher from 1934 until 1973, and she also worked as a journalist and writer during those years and beyond. Tales from the Story Hat was her first published book, and it was both a critical and commercial success. The book is no longer in print, but used copies are abundantly available, as is also the case with the sequel: More Tales from the Story Hat.

There are nine tales in the book, and Aardema provides detailed bibliography for each: three come from Henry M. Stanley's collection of stories from the Congo and Uganda first published in 1873 (a remarkable book that I'll write about in a separate post); since Stanley's book is in the public domain and available online, you can compare Aardema's adaptation of her sources. Another story is adapted from a legend reported in Mary Kingsley's Travels in West Africa, also available online, and in this case Aardema has taken a very sparsely told Igbo story and turned it into a really exciting story ("Wiki the Weaver"). Aardema also took a Fang story reported in a novel, Stinetorf's Beyond the Hungry Country, published in 1984 which you can read online at the Internet Archive if you want to compare Aardema's story to her source material. Two more of Aardema's stories comes from booklets published in Liberia which are hard to find anywhere, so that makes her stories here especially valuable, giving us (indirect) evidence for some Liberian folktales that are hard to track down otherwise. I'll have more to say about one of those Liberian stories below; it is a really exquisite fairy tale that seems to me ideal material for prompting students to write their own fairy tales using the same formula.

Meanwhile, in addition to those African sources, Aardema includes two stories from "LoBagola" (Joseph Howard Lee), one of the most fascinating literary tricksters of the 20th century. I'm not going to try to provide an account of LoBagola's life and career here, but he has a Wikipedia article. One of my future projects is to try to do a motif analysis of LoBagola's published stories to get a sense of just what Joseph Howard Lee took from African folktale traditions (that might have been known to him directly or indirectly) as well as elements of his own imagining. I have a long way to go in developing my motif catalogs, but I definitely think LoBagola merits our attention as an African American storyteller as well as being a trickster in real life. In any case, at the time Aardema wrote this book, she did not question LoBagola's self-proclaimed identity as a West African "savage," including his stories side by side with the stories she retold from African sources.

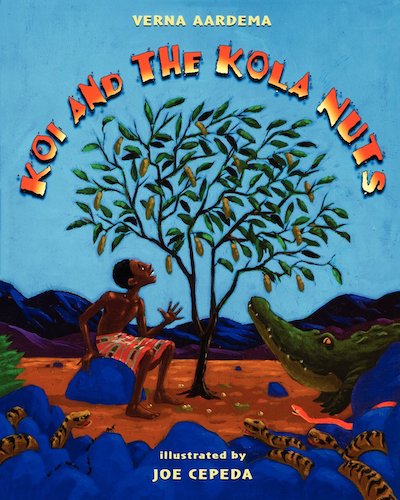

I'll close with some comments about the really exquisite fairy tale that Aardema tells from a Liberian source: Koi and the Kola Nuts. The story has many distinctive African features, like the kola nuts of the story's title, which might be of special interest to students who are fans of cola; more about that at the BBC: The little-known nut that gave Coca-Cola its name.

Here's how the fairy tale takes shape:

1. Village chief dies, and his sons inherit his property. The youngest son, who is a little guy and underrated by all, is away hunting and comes back to find nothing is left to give to him... except for a scraggly kola-nut tree. The boy, Koi, picks all the nuts, puts them in a bag and sets off to find a village where he will be respected as the son of a chief.

2. Along the way, Koi meets a snake who needs some kola nuts as medicine; he shares his nuts with the snake.

3. Next, Koi meets some ants who stole the devil's kola nuts and need to pay them back; he shares nuts with the ants.

4. Next, Koi meets an alligator who killed a dog and ate it, and now he has to make restitution in the form of kola nuts; he gives the last of the nuts to the alligator.

5. Koi arrives at a village where they mock him for his small size and poor appearance, even though he insists he is the son of a chief. The chief of that village sets Koi some impossible tasks.

6. I'm not going to spoil the whole story but suffice to say the snake helps him complete the first task.

7. The ants help him complete the second task.

8. The alligator helps him complete the third task.

9. The village chief decides to give Koi half the kingdom, recognizing that he is truly a great man after all.

10. The village chief also gives Koi his daughter in marriage, so Koi becomes not just a co-chief but also son-in-law.

I really like the fact that children who might only be familiar with European fairy tales will grasp the ways in which this West African story from Liberia shares the same overall "story form" as fairy tales they might already know.

Then, once students see that fairy tales have a "form" (formula), they can create their own, with their own heroines and heroes, their own magical helpers, their own quests and tasks, their own rewards, etc.

Of all the stories in this book, this one seemed the most likely to use a kind of writing prompt for students. There's also a single-story book edition of Koi and the Kola Nuts by Verna Aardema which is not available at Internet Archive but, interestingly, a version by Brian Gleeson with illustrations by Reynold Ruffins which is available for digital lending: here's the link. I'm surprised, and disappointed, to see that Gleeson does not credit Aardema, or any other source, for the story. The details which he shares with Aardema's story make it pretty clear (?) that she must have been his source. Wikpedia identifies the story as an Igbo story from Nigeria, but provides no citation for the source at all. If I find more information about the source of this story (I do have some Liberian folktale books yet to explore), I'll update this post.

Aardema's book:

Gleeson's book:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are limited to Google accounts. You can also email me at laurakgibbs@gmail.com or find me at Twitter, @OnlineCrsLady.