There are still a few more days in November, so that means a few more days of posts here about public domain African folktale books at the Internet Archive, and what I wanted to focus on today is a genre of books from South Africa that have a lot in common with the "Uncle Remus" books published by Joel Chandler Harris in the United States: the stories of African people are put inside the framework of a white family, providing a paternalistic sentimental picture of the African storyteller and his white audience.

Like the Harris books, these books provide valuable testimony about traditional African stories that were being told a hundred years ago, but the condescending framing of the stories can be hard to take. You can get a sense of the sentimentalizing of the colonial occupation here in the words of Sanni Metelerkamp in the introduction to his book: "scenes flit across the lighted screen of Memory, noontides of tropic heat with all the world sunk in a languorous slumber... And always, part and parcel of the passing panorama, the quaint figure of the old Native with his little masters."

In a word: ugh. But if you can strip away this colonial whitewashing, you will find echoes of the African storytellers even in books like these, just as in the Brer Rabbit stories recorded by Joel Chandler Harris in Georgia.

I'll start with the oldest: Old Hendrik's Tales by Arthur Owen Vaughan, published in 1904.

These links will take you to the specific stories at Internet Archive: Why Old Baboon has that Kink in his Tail. /

Old Jackal and Young Baboon. /

Why Old Jackal Danced the War-Dance. /

How Old Jackal got the Pigs. /

When Ou’ Wolf built his House. /

Ou’ Wolf lays a Trap. /

Ou’ Jackalse takes Ou’ Wolf a-Sheep Stealing. /

When the Birds would choose a King which tells also why the white owl only flies by night. /

Why Old Jackal slinks his Tail. /

Why Little Hare has such a Short Tail. /

The Bargain for the Little Silver Fishes. /

Why the Tortoise has no Hair on. /

Why the Ratel is so Keen on Honey.

Old Hendrik is a Khoekhoe storyteller, and this book uses some eye-dialect to try to convey Hendrik's style of English. He regrets that his audience can't speak his language ("taal" is Afrikaans for language), so he has no choice but to tell the stories in English: "If you little folks only knowed de Taal! It don't soun' de same in you' Englis' somehow."

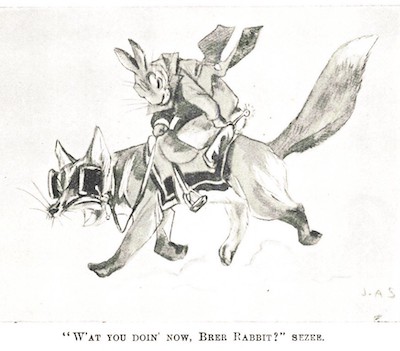

This book has illustrations by the British artist James A. Shepherd who also did the illustrations for the British editions of Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus books: Uncle Remus in 1901 (just before this book) and Nights with Uncle Remus in 1907 (just after this book), all done in a very similar style. Compare, for example, jackal riding the wolf from that book's cover with the story of Brer Rabbit riding Brer Fox here:

Jackal is the main trickster in the book, although there are also stories about the trickster Rabbit too. Here is Shepherd's Rabbit from a South African story (feeding Tortoise from a calabash):

And here is his Rabbit from an American story (with Lion):

Lions are a natural part of the landscape of African storytelling, of course... but not in Georgia. My own interest in African folktales began with the African storytellers in the Americas and specifically how the African folktales were told and retold in the southern United States. When Shepherd was reading these stories and working on these illustrations, I wonder how much he thought about the enslavement of people from Africa and how the stories came from Africa to the Americas centuries ago!

The next book is Outa Karel's Stories: South African Folklore Tales by Sanni Metelerkamp.

As you can see, the sentimental focus of the book is the young white child listening to the stories, just as Joel Chandler Harris focused on the young white child who was Uncle Remus's audience in those books. Outa Karel, "Old Man Karel," is the storytelling equivalent here of Uncle Remus. You really have to wonder that the author did not stop, even just for a moment, to think about the first appearance of Outa Karel in the book: "he looked like nothing so much as an ancient and muscular gorilla in man's clothes, and walking uncertainly on its hind legs." That's really bad; worse than Harris...

So, like I said above: the framing of the stories in these books is really repugnant, and we're talking here about a book published just a century ago. But I'm here for the stories, so here are the story links for this book: How Jakhals Fed Oom Leeuw /

Who was King? /

Why the Hyena is Lame /

Who was the Thief? /

The Sun /

The Stars and the Stars’ Road /

Why the Hare’s Nose is Slit /

How the Jackal got his Stripe /

The Animals’ Dam /

Saved by his Tail /

The Flying Lion /

Why the Heron has a Crooked Neck /

The Little Red Tortoise /

The Ostrich Hunt .

The illustrations for this book are by Constance Penstone. There aren't many illustrations, but they are a welcome addition to the book, both for her drawings of the animal characters and also the people:

The third book in this series is Koos, the Hottentot: Tales of the Veld by Josef Marais, a more recent book, published in 1945, but identified at Hathi as being in the public domain.

As you can see, these stories feature traditional characters from San and Khoekhoe mythology and folktales: Raincow and Baboon King /

The Honeybird and the Mamba /

The Queen Serpent of the Rivers /

Windbird and the Sun /

Echo and Mirage /

Hammerhead and Bullfrog /

Moon and the Rock Swallows /

Porcupine and Dassie /

Mantis, the Hottentot God /

Dawn and Dusk.

This book is illustrated by Henry Stahlhut, including some color illustrations, like this one of Mantis and Porcupine:

In this book, there is no attempt at reproducing any kind of African speech or dialect, although some Khoekhoe words are included, as when Koos is talking to the sheep, but when he is telling stories, Koos speaks a very high-style English. There are a large number of Afrikaans words in the book too, with a detailed glossary and pronunciation guide in the back (the other books also contain glossaries of Afrikaans words). This book also includes music both in the stories, and with an appendix of songs in the back.

So, proceed with caution, but there is a lot to learn in these three books, both about African folktales, and also about the pervasive white supremacy of colonial culture in Africa too. (And consider this post a promise of many more posts to come about the legacy of Joel Chandler Harris in the United States too!)

by Arthur Owen Vaughan

by Sanni Metelerkamp

by Josef Marais

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are limited to Google accounts. You can also email me at laurakgibbs@gmail.com or find me at Twitter, @OnlineCrsLady.