You will find ten stories in this book taken from old collections of South African folklore: Callaway's Nursery Tales, Traditions, and Histories of the Zulus, Honeÿ's South African Folktales, Kidd's The Bull of the Kraal and the Heavenly Maidens, Torrend's Speciments of Bantu Folklore from Northern Rhodesia, Werner's Myths and Legends of the Bantu, and Brownlee's Lion and Jackal with Other Native Folk Tales from South Africa. All of those books except for Brownlee's are readily available online. One of them, Callaway's Nursery Tales, has facing Zulu text with the English translation.

These are all old books, but especially with the inclusion of beautiful art by the Dillons, the stories very much take on new life. I cannot say enough good things about their amazing work, as you can see even just starting with the cover of the book; here you can see how it works as a two-page spread:

So, I've picked four stories that I want to focus on this week and I'll be updating this post with my notes each day. Meanwhile, for today, I want to start with the title of the book, which is taken from the words of the San storyteller, ǁkabbo, whose stories were recorded by Wilhelm Bleek in Specimens of Bushman Folklore. Here is what Aardema says in the opening of the book:

A hundred years ago the Bushman storyteller, Hiddoro Kabbo, said that when one has traveled along a road he can sit down and wait for a story to overtake him. He said a story is like the wind. It comes from a far place and it can pass behind the back of a mountain. Here, one has only to turn the page to allow a story to overtake him.

To find out more about ǁkabbo and his work with Bleek, I highly recommend the detailed and deeply moving, and heartbreaking, account provided by J. David Lewis-Williams in Stories That Float From Afar : Ancestral Folklore of the San of Southern Africa, which is also at the Archive. The title of that book comes from the same source that Aardema invokes; here is how ǁkabbo's words were recorded by Bleek in romanized transcription, plus an English translation. The text runs for several pages as ǁkabbo grieves for his separation from his people (click for a larger view; the text begins on p. 298):

And here is the portrait of ǁkabbo that appears in the book:

So while, like Aardema, I am glad we can read the stories that have been preserved and printed in books, that only happened in a context of cultural genocide and the apocalypse that white colonialism brought to the African continent. We are reading children's books in Anansi Book Club, with all the joy and fun that children's books can bring, but especially since Aardema herself has invoked ǁkabbo's words in the title of her book, we should remember ǁkabbo and all the other nameless, silenced storytellers too.

So, the first story I want to focus on here is "This for That," and as you can perhaps guess from the title it is a trading-up type of chain tale, a very popular type of trickster tale in Africa. This version of the story, however, is especially elegant: Rabbit does succeed in trading up, but he is ultimately going to have to reckon with Ostrich again at the end of the story, after Ostrich's feather begins his trading-up adventure. You can read Aardema's original source here, a Tsonga story from Zimbabwe in Torrend's Bantu Folklore, which has the Tsonga text and an English translation: My Berries! Aardema changed the crane of the source story to an ostrich, and she changed the ending, bringing the bird back into the picture. In the source story, the beasts fired a cannon at the bad rabbit and killed him! Here is how the Dillons depict the trickster Rabbit trading the feather as the chain of trades begins, and then Rabbit riding away on the Ostrich, clutching his ill-gotten gains:

I wish Aardema provided more detailed notes about her own storytelling process, but at least we can compare her version to the source story and see the changes she made.

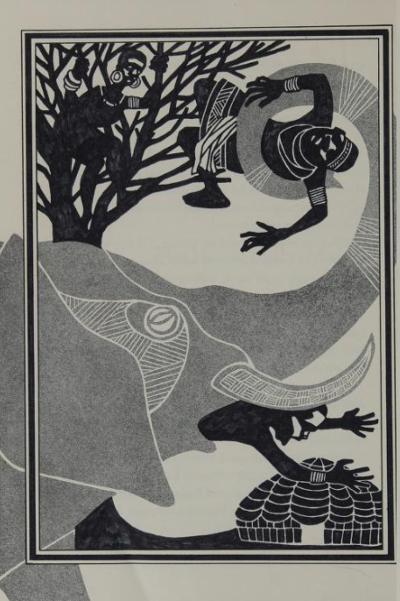

In the story Saso and Gogwana the Witch, you will see one of the most popular animal story types, featuring a loyal and brave dog who, even though tied up, manages to break free and save the person(s) trapped high up in a tree that the witch (or wizard or monster) is about to chop down. But defeating the witch is not the end of the story here: the witch has... family! The source for this story is an Ndau legend, How Skin-Sore Killed a Cannibal, retold in Dudley Kidd's book The Bull of the Kraal and the Heavenly Maidens. Here is how the Dillons show the dog coming to the hero's rescue:

Today's story is one of my favorites: the swallowing-monster story, this time in the form of an elephant, where a brave woman rescues her children from inside the monster. You might recall this monster-elephant from Mhlophe's Stories of Africa book. In Aardema's book, it is called The House in the Middle of the Road. Her source is the Zulu version recorded by Callaway: Unananabosele. The art by the Dillons is amazing! Here is the elephant swallowing the children:

And here you can see the people inside the monster elephant:

Another story I really liked here is an animal tale about the trickster jackal: How Blue Crane Taught Jackal to Fly. This is a popular folktale, and sometimes it ends with jackal tricking the crane... but in this version the crane gets the last laugh as she teaches jackal to fly (not!). Aardema's source for the story is Brownlee's book, which is not online; I own a copy but my personal books are in storage right now, so I can't confirm if this ending of the story is in Brownlee or if it comes from Aardema. As soon as I get access to my personal books again (in a couple months I hope!), I'll update the post with the answer to that question. Meanwhile, Aardema's version of the story is very satisfying (the trickster tricked!), and here's how the Dillons show the jackal first tricking the foolish dove:

Then the blue crane takes the jackal for a flying lesson; if you look at the background image, you can also see the jackal plunging to the earth. The way the Dillons use the two images superimposed is a great technique throughout this book:

So, those are just four of my favorites, and of course all the stories in this book are wonderful, along with the likewise wonderful art by Leo and Diane Dillon.

I want to finish up this week with some information about both Verna Aardema and Leo and Diane Dillon. Aardema was a prolific (PROLIFIC) writer of African folktale books, dating back to From the Story Hat in 1960, when she was already 49 years old (she was born in 1911 and died in 2000). The opening five articles in my Reader's Guide to African Folktales at the Internet Archive provide an overview of her work.

For the remarkable work of Leo and Diane Dillon, this interview gives some insight into their work: The Third Artist Rules.

The the "third artist," they mean the way their work in collaboration took them places that they never would have reached individually; you can find out more at Wikipedia, where they share an article together, as it should be. And I love this statement by Diane Dillon in defense of the art of illustration:

We take great pride in illustration and the fact that we are illustrators. We've never thought there is a difference between 'fine' art and illustration other than good art or bad art. One publisher once complemented us by saying that they were going to give us credit on the book jacket as 'paintings by the Dillons,' rather than illustrations. We said, 'No, we want illustrations.' That's what we are, that's what we do, and we're very proud of it. If it's good, so much the better that it should be called an illustration

You can also explore their work at D. Michelson Galleries online where you can find this gorgeous illustration for Leo & Diane Dillon: On the Wings of Peace: Writers and Illustrators Speak Out for Peace, in Memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which is also at the Archive. :-)

So, if you want to get to know the Dillons' work, this book is a perfect place to start:

by Verna Aardema

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are limited to Google accounts. You can also email me at laurakgibbs@gmail.com or find me at Twitter, @OnlineCrsLady.